The tradition of black gun ownership in America has always been different. The “black codes” were implemented in many states, designed to keep blacks from exercising their right to keep and bear arms. In Florida, for example, whites could enter black-owned homes and search for weapons without a warrant. In Louisiana, blacks could be stopped and searched for weapons at any time. If they refused to comply, they could be shot.

Over the years, even prominent black leaders were denied their Second Amendment rights. In 1956, The Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., was famously denied a concealed carry permit by the Sheriff’s Office in Montgomery, Alabama even after his home was fire-bombed. Sheriff’s officials found King “unsuitable,” for a carry permit.

While King was famous for espousing non-violent political action, he was also a gun owner who believed in self-defense.

One of King’s contemporaries, Malcom X, was a strong Second Amendment supporter.

“The Constitution of the United States of America clearly affirms the right of every American citizen to bear arms. And as Americans, we will not give up a single right guaranteed under the Constitution,” he said.

As part of Black History Month, the Second Amendment Foundation is commemorating the work of three Second Amendment scholars whose advocacy and lifelong commitment to the right to keep and bear arms has benefitted everyone who owns a gun.

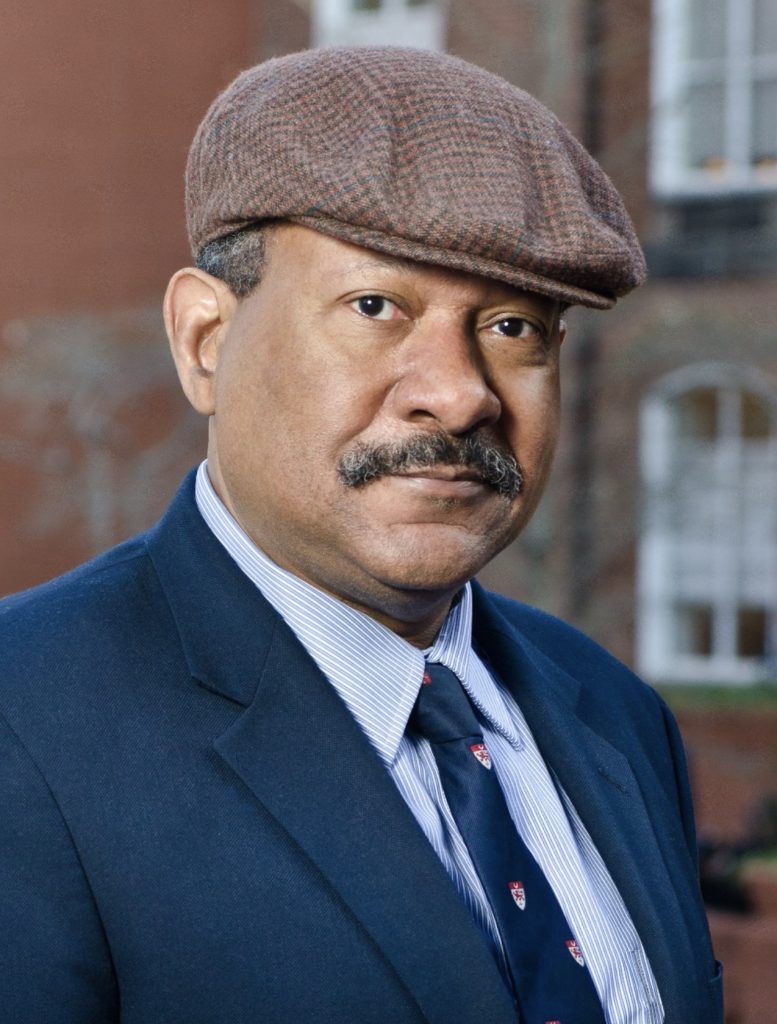

Professor Robert J. Cottrol

Bob Cottrol is the Harold Paul Green Research Professor at the George Washington University Law School. He joined the law school in 1995 after teaching stints at Rutgers University and Boston College. His books and scholarly articles have won awards too numerous to mention and have been cited by other academics and high courts, including the U.S. Supreme Court, the Third Circuit Court of Appeals and the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

Professor Cottrol consented to answer questions for this story.

Q: Historically, how did the tradition of arms for black Americans differ?

A: “Obviously during slavery there were prohibitions on blacks having guns. These fell into two categories: Both slaves and free blacks couldn’t have guns. In the Northern states – free states – the right to keep and bear arms was generally unimpeded, and blacks were able to resist racist attacks in Providence, Rhode Island, Boston, Philadelphia and various other cities.”

Q: Does this influence black gun ownership today?

A: “More, of course, was what happened after the Civil War. There were former Confederate states casting Black Codes, which prohibited gun ownership, which the Fourteenth Amendment was meant to correct. Then you have a tradition in the Southern States – from 1870 to the early 1970s – of resistance to racial violence, where blacks couldn’t depend on local police for protection from the Ku Klux Klan and the federal government lacked the power to protect people against private violence. There was a tradition of black people defending themselves and defending their communities. This heightened after World War II. Veterans were very militant about defending their rights. There was a second birth of that tradition of arms in terms of the Civil Rights movement, including, ‘Deacons for Defense and Justice,’ in Mississippi and other states. The Deacons said, ‘We know how to use arms, and by God, we will.’ These were WWII and Korean War veterans who knew how to use rifles, which they were able to get from the NRA.”

Q: Is firearm ownership lower among blacks than whites?

A: “It is, though it’s hard to say why. There is no general firearm registry, thank goodness, so we don’t really have a full picture. The black population is more urban than the white population. Generally, firearm ownership is lower among urban populations. But more and more we’re seeing that firearm ownership is becoming less of a rural heritage. It’s more a matter of people in cities and suburbs wanting to defend themselves – folks who didn’t grow up duck hunting.”

Q: What issues to black gun owners face today that the rest of us may take for granted?

A: “Some of the issues you might have. There’s still a certain amount of just plain ole discrimination coming from gun control officials and those who support gun control. I was just reading where they’re still trying to ban guns in public housing. There are real attempts to suppress gun ownership in urban areas. If you look at New York and others with large black populations, they still have a legacy of trying to prevent black people from owning guns. I wonder to what extent is there a tendency for police to assume that an armed black person is an honest person just trying to defend himself.”

Q: What is the biggest threat facing our Second Amendment rights today?

A: “One that we’re seeing in a lot of states, certainly on the West Coast, you have people saying outright that they are going to defy Heller and Bruen. They’re saying, ‘Yeah, the Supreme Court said that, but we can tie this up in knots and we don’t care about that.’ Also, it’s frightening to see the degree to which the ‘assault weapon’ fraud has gotten legs. If you look at the actual figures, the number of people killed with rifles is miniscule, yet legislatures are passing this nonsense legislation. Again, in this area, we hope the Supreme Court moves swiftly.”

Q: Do you consider yourself a black Second Amendment advocate or a Second Amendment advocate who just happens to be black?

A: “I am a Second Amendment advocate, but I’m not sure how you disentangle those two things. It’s simply a part of who I am. I think the black experience should inform everyone about the question of arms and rights, and the importance of arms in preserving rights. We should learn from the experience of all people – the Jewish experience and others – what happens if you’re not able to defend your basic right to live.”

The Reverend Kenneth V. F. Blanchard

Kenn Blanchard is hard to pigeonhole: Second Amendment advocate, career federal police officer, U.S. Marine, firearms instructor, and of course award-winning author.

Blanchard’s “Black Man with a Gun: A Responsible Gun Ownership Manual for African Americans,” should be required reading for every new shooter, regardless of their race. The first edition has FAQs and a glossary for new gun owners. The second edition contains updated information.

“When I started in 1991, I looked around for a template. The last thing I saw written was “Negros with Guns.” No one really remembered it. It was published in 1962, so I did an updated version,” Blanchard told the Second Amendment Foundation.

Professionally, Blanchard’s book put him in a precarious situation.

“There were problems with my employment. I did all this at great risk. The intelligence community, at the time, was very afraid of an insider threat. They saw this guy who was a gun-rights activist, and they knew what they had taught me. I had a tail on me for a while. I didn’t get promoted. At the same time that I advocated for the rights of everyone, I was terrified,” he said.

Today, Blanchard believes black gun ownership equals that of other Americans, but it was not always so.

“When I began 30 years ago there was a lot of stigma, racist fear, racism and the expectation that white America was keeping us back. Among black Americans, there were fears and myths and cultural conditioning, that if you had a firearm, you got it illegally. That’s what I was dealing with then,” Blanchard said. “This cultural conditioning said you had to stay unarmed to stay out of trouble. Also, once we left the plantations and sharecropping, it was considered unsophisticated to hunt or bring a gun into the city – leave them guns alone. Everything we did was undercover. Veterans weren’t allowed to pro-gun in public. It was almost like a secret club. When I popped up, I didn’t know my own history, stigma, stereotypes or fears. All I wanted to do was be a trainer, but I had to undo 300 years of cultural conditioning.”

Blanchard believes the biggest threats facing our Second Amendment rights are “fear and apathy.”

“We are just one politician away from trouble,” he said. “All they need is one well-versed anti-gunner. For example, if Taylor Swift got on the anti-gun bandwagon, it would really hurt us. It was Oprah during my time.”

In August 1997, Blanchard received the Gun Rights Defender of the Month award from the Citizens Committee for the Right to Keep and Bear Arms.

In nominating Blanchard for the award, CCRKBA’s then-Public Affairs Director, John Michael Snyder, pointed out Blanchard’s “demonstrated leadership on behalf of the individual right of law-abiding citizens to keep and bear arms in the Washington, D.C. area.”

“In fact, he has come up with a unique concept and is working now to implement it. He sees the need for cooperation among local pro-gun rights organizations at the regional level. He already is working for such cooperation in the Washington, D.C.-Maryland-Virginia region,” Snyder said in a statement. “To implement this concept, he called a “Shooting for Peace Conference,” an all-day gathering to establish peace among the various pro-gun groups in the area. It was held at the New Carrollton, Maryland Public Library on June 21. I was glad to be there and hope that other pro-gun spokesmen from around the country will pick up on Kenn’s idea and work in a similar manner in other parts of the United States.”

Professor Walther E. Williams

Walter Williams was a fierce Second Amendment advocate and an influential economics professor at George Mason University. He authored an award-winning column, which was syndicated nationally and appeared in more than 150 newspapers.

An Army veteran, Williams taught his students that discrimination was “merely a synonym for choice. Each of us discriminates when we choose a college, a spouse, a church, and so on. So, the question arises: What are the conditions that allow space for racially discriminatory actions to breathe?”

Williams died in 2020 at the age of 84.

As an economist, he championed the Free Market. As a Second Amendment advocate, Williams pulled no punches. He considered every single anti-gun law an infringement of our Second Amendment rights.

His columns were scathing, as Congressman John Lewis, a Democrat from Georgia, discovered in January 2013, after he said, “The British are not coming. We don’t need guns to kill people.”

Williams responded with quotes from our Founding Fathers, including one from Alexander Hamilton: “If the representatives of the people betray their constituents, there is then no recourse left but in the exertion of that original right of self-defense which is paramount to all positive forms of government.”

Williams cited another well-known Democrat in his kill-shot of Lewis’ argument.

“Rep. John Lewis and like-minded people might dismiss these thoughts by saying the founders were racist anyway,” he wrote. “Here’s a more recent quote from a card-carrying liberal, the late Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey: ‘Certainly, one of the chief guarantees of freedom under any government, no matter how popular and respected, is the right of the citizen to keep and bear arms. The right of the citizen to bear arms is just one guarantee against arbitrary government, one more safeguard against the tyranny which now appears remote in America, but which historically has proven to be always possible.’”

Senator Ted Cruz, R-Texas, said in a statement mourning Williams’ death that his “legacy will endure as we continue to fight for liberty.”

“Born in the projects of Philadelphia to a single mother of two, Walter went on to achieve the American dream as a brilliant economist, accomplished professor, and profound author,” Cruz wrote. “As a teenager, I frequently read his work and was moved by his fierce defense of free markets and the virtues of liberty.”

The Second Amendment Foundation’s Investigative Journalism Project wouldn’t be possible without you. Click here to make a tax deductible donation to support pro-gun stories like this.

This story is part of the Second Amendment Foundation’s Investigative Journalism Project and is published here with their permission.

[Prof. Bob Cottrol, the Harold Paul Green Research Professor at the George Washington University Law School.}

“Q: Is firearm ownership lower among blacks than whites?

A: “It is, though it’s hard to say why. There is no general firearm registry, thank goodness, so we don’t really have a full picture. The black population is more urban than the white population.”

I suspect the reason is largely cultural. Look how black gun ownership is seen in the media, as mostly a gang violence thing. There may be blacks would very much like to own guns, but their own friends and families may try to pressure them not to, sad to say…

Hey, Geoff,

There is another issue, mostly statistical (although also somewhat cultural) in compiling the numbers. There is a relatively statistically high incidence of gang involvement among black, inner-city yoots – and I’m fairly certain they don’t show up in any official statistics of “black gun ownership rates”. Also, I think there is a certain cachet among gangbangers to NOT have a legal gat, so they can (i) be more immune from police seizures, and (ii) probably most gangbangers would be “prohibited purchasers”, for one reason or another. The cultural thing probably does have an impact, as well.

Great post.

This reminds us that you really can’t pigeonhole academics by race. See, e.g., Thomas Sowell, John McWhorter.

One of my favorite undergrad professors (John Sibley Butler) was the *fourth* generation in his family to teach at a university. He was also one of the first to integrate LSU in the sixties . . . where his roommate was David Duke (whom he has publicly debated many times since). Did a tour in ‘Nam (as a LRRP squaddie) after he graduated, then got his PhD in sociology (data driven), with a specialty on military race relations, and also applied his hard science approach to business (and made a fortune in the process).

He was brought in as a guest to my freshman Plan II (UT lib arts honors program) seminar, where I was blown away with his DATA-DATA-DATA approach to hot-button race issues. Took as many classes as I could from him. Decades later, he brought me in to guest lecture to *his* business classes.