My first exposure to virtual reality headsets was back in the early 1990’s. While attending the Comdex computer trade show in Las Vegas, a hot topic of attendee conversation was a VR arcade game, a FPP shooter called Dactyl Nightmare made by a UK company (Virtuality) being demoed at Ceasar’s Palace.

The dedicated game units were massive (at least compared to other arcade game consoles) with very heavy and bulky VR headsets that, like the handheld game controllers, were hardwired to the unit. Tracking was done by sensors in a circular rail that you stood in, which also served as a safety cage of sorts.

The graphics (372 x 250 per eye) and gameplay were incredibly crude by today’s standards and the tracking had more than a bit of lag…enough to induce nausea in some players. And the equipment wasn’t exactly robust. In the three days I was at that Comdex, I suspect the demo system was down about as much as it was up and running.

Nevertheless, like just about everyone else who stood in the long lines to try it, I found it to be mind blowing. For someone who was used to playing video games at the time on a 19-inch screen in front of you, with your movements and views controlled by keystrokes, a mouse, or a joystick, having your view change almost instantly based on where your head or body was located/pointed (along with the multichannel, directional sound effects) created the immersive illusion of actually being “in” the game.

When the pterodactyl dove towards players in the game, players would instinctively duck, creating an amusing spectacle for onlookers. It occurred to me and others that if (when) the technology significantly matured, a system like this might actually go beyond video gaming and become a way to do serious firearms training.

While the buzz at that Comdex was that this kind of VR would be the “next big thing,” the next three decades proved largely disappointing. While the military and the aviation industry have since made extensive use of dedicated aircraft, tank, crew served weapon and related simulators, until recently consumer grade VR was typically expensive, clunky, finicky, and graphically underwhelming when compared with other computer and console games, and thus really never caught on.

Simulated firearms training during this period instead developed along the path of systems that used laser-firing devices (SIRT-type weapons or modified real ones), video projectors, and shot-sensing cameras.

For small arms training, commercial systems like FATS, LaserShot, VirTra, and SES provided varying degrees of “reality’, including “pain penalty” options for stress inoculation training, and have been widely used by both law enforcement and military trainers.

The problem is such projector-based systems have typically been quite expensive and often require a fairly large room or dedicated space, and many of these vendors restrict their sales to military or law enforcement customers only.

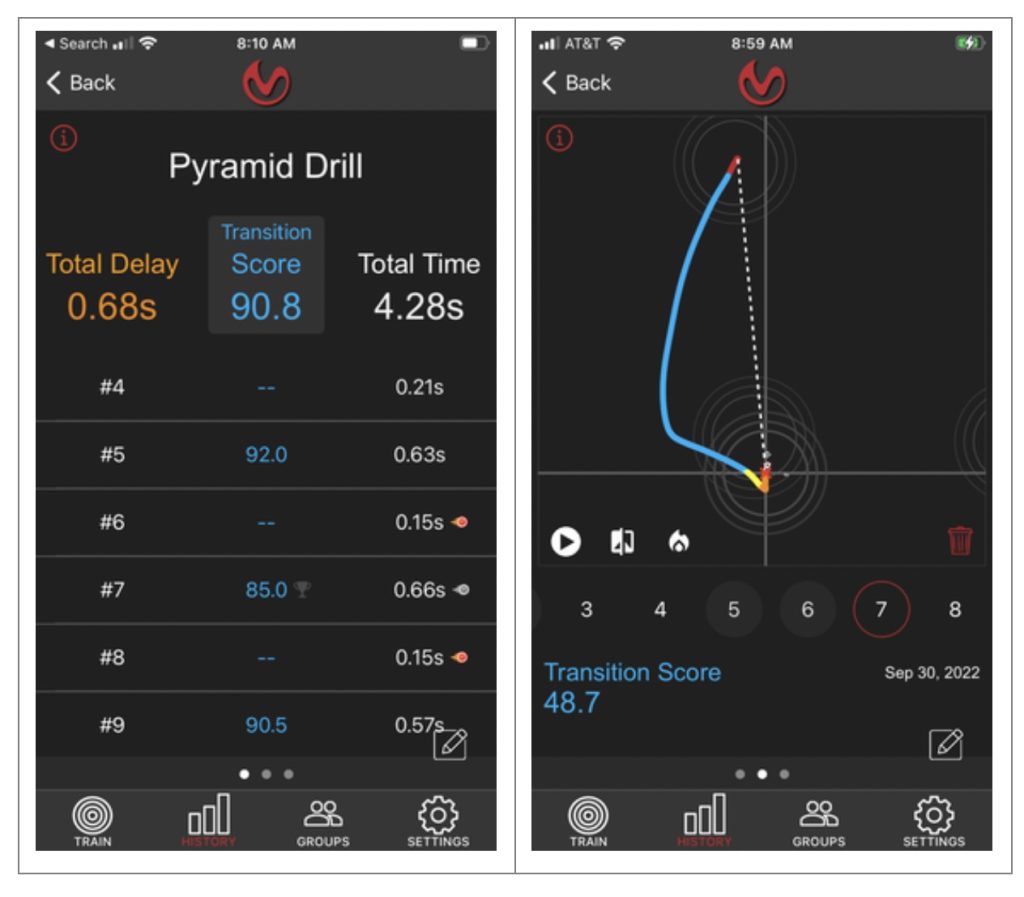

Consumer grade firearm simulators (such as those by Mantis, iMarksman, Strikeman, and DryFireMag) also use laser emitters and either shot cameras or laser-sensing targets, which make dryfire practice much more fun and provide valuable feedback.

One of the most advanced dryfire systems is the BlackBeardX by Mantis, which replaces the bolt carrier group and magazine in a standard AR.

When the weapon is dry fired, the BlackBeardX emits a laser pulse through the barrel (the laser can be zeroed to the point of aim), and when the trigger is released, a servo physically resets the hammer and sear. The trigger weight and break is thus identical to the host weapon in its “hot” configuration, as is the overall weight and balance of the weapon.

Best of all, there’s no need to charge the weapon between shots. You can dry fire as fast as you can pull the trigger, allowing you to practice target acquisition and transition drills without breaking your grip or sight picture.

Like the MantisX system, BlackBeardX tracks precisely where the weapon is pointed throughout the drills, and also provides smart analytics and detailed feedback on your shooting mechanics. Indeed, it’s now being used by the US military to teach marksmanship fundamentals. (Look for a more comprehensive review of the BlackBeardX in a future SNW article.)

But while various consumer laser dryfire products can provide an excellent way to practice your draw, sight picture, trigger press, target transition, and mechanics while developing muscle memory — and some even provide a pretty good simulation of shooting steel targets (especially that viscerally-satisfying “ping” we all love) — they can definitely get boring after a while.

At the end of the day, you’re still dry firing at a static target, projected image, or computer screen.

The Rise of Meta Quest

While the Meta Quest VR headset (formerly known as the Oculus Rift) has been around for several years, the release of the Meta Quest 3 (street price about $500) and the resulting price drop of the older Meta Quest 2 (street price about $200) have kicked the home VR market into a higher gear.

Both provide excellent graphics and worry-free head/body and controller tracking in a wireless package (although you can also connect them to a computer via a USB C cable) at a very reasonable price. And unlike earlier home VR systems like the HTC Vive, there are no other external tracking sensors. All you need is the headset and the controllers, and you’re good to go.

Indeed, with the Meta Quest 3, in some programs you don’t even need a controller. The cameras built into the headset track your hand motions and use those as the game controller.

With an affordable, stable, and reliable VR headset platform now available, developers have started coming out with applications and peripherals squarely aimed (so to speak) at the firearms community. Certainly, there have long been plenty of “shooter” video games available for VR platforms (e.g., Ghosts of Tabor, Contractors, etc.). But aside from a few high end commercial arcade products like Striker VR’s Mavrik Pro (which also features simulated recoil), all of them merely use the system’s controllers (including their toylike electronic switch “triggers”) for the simulated weapons, rather than peripherals that either use actual firearms or closely resemble the real deal’s weight and feel.

While that’s perhaps entertaining as a video game, I don’t consider such “shooters” to be viable training vehicles for developing or practicing actual firearms skills.

One notable exception: LeadTech’s Clazer system for the HTV Vive system, a skeet/trap/sporting clays simulator and trainer which mounted the VR controller/tracker to the user’s actual shotgun. Alas, that product hasn’t been updated in several years, although LeadTech principal Chip Northrup has indicated to me that a port of Clazer to the current Meta Quest platform may be in the works.

Which Meta Quest headset would you need for home firearms training? While the Meta Quest 2 is definitely usable, I’d recommend spending a little more coin and getting the Meta Quest 3.

As indicated in an earlier SNW article, this newer version has significantly better graphics and a faster processor. One user cogently observed that using the Meta Quest 2 is like having 20/30 vision, whereas the latest model is like having 20/20. Additionally, the multiple forward-looking cameras on the MQ3 allow for better augmented reality uses.

The one thing I (and most other users) definitely don’t like about Meta Quest headsets are their flimsy head straps. Fortunately, there are a variety of inexpensive replacement options. I prefer the Kiwi Comfort Headstrap ($29), which is very comfortable and can be adjusted and tightened with a knob on the back the same way you would a hardhat or welding mask.

While both headsets can be worn over eyeglasses, corrective lens inserts are readily available for very reasonable prices, and they make these headsets much more comfortable. (Note: If, like me, you wear bifocals or progressives, such lenses only need your distance prescription.) They’re highly recommended if you have old eyes.

In the next two parts of this series, I’ll review the two current leaders in the home VR firearms training space, ACE Virtual Shooting and GAIM. Both of these are designed for the Meta Quest platform and have dedicated controllers that more closely simulate or even use an actual firearm. They also have programs that more closely simulate the mechanics of actual shooting, and provide valuable feedback for training. In Part IV, I’ll discuss where home VR firearms training may be going in the future…and where I’d like to see it go.

I was an expert marksman by the time I was 15…thanks to Nintendo’s Duck Hunt.

I can go back further than that. I was an expert from the old school “Duck Hunt” game back at my local Straw Hat Pizza Parlor in the early ’80s. Enough quarters will ensure a back full ‘o ducks.

Or even further . . . .

In Japan in the early 1970’s, there was a glut of bowling alleys (bowling was a huge fad in Japan in the 1960’s that faded out). A company called Nintendo came up with a system using screens, projectors, light-emitting simulated shotguns, and cameras that could be installed in these underutilized bowling alleys for simulated skeet shooting. They later were able to shrink the package enough that it could be installed in arcades.

I recall shooting on one at the Landa Park Resort (New Braunfels, Texas) circa 1974.

If any of you in the Central Texas area are (or have been) serious competitive clay shooters (skeet, trap, 5-station, sporting clays, etc, I’d like to get with you to collect some additional data for Part III (which is the review of the GAIM system, including its clay target simulators). If you are interested, please drop a note here in the comments.

Thanks Louis – We are totally focused on building military VR marksmanship simulators to teach lead on moving targets.

Follow us on LinkedIn – https://www.linkedin.com/in/james-northrup-25b59710/ Or at https://www.leadtech.co/

Once we have the military trainer finished, will go back and redo Clazer for the MQ3